Digitization, when archiving collections, contributes to preserving historical design, improving access, and permitting a greater amount of control when managing objects of cultural heritage. However, the scale of impact is constrained by the physical limitations of the object being cataloged, including: the sophistication of optics, what machine learning is being used by the scanner (if any), the organization of the digital platform, and ultimately how end-users are prepared in using this final product. Swiss startup ARTMYN maintains these high standards to create a more individually personalized digital object for their clients. This process transcends the traditional scope of collections and stewardship, creating new standards for the art marketplace, and possibly new modes of viewership in museums. ARTMYN builds a topographic map to fully represent a tangible object through contours, color, and light and this digital media can then be interacted with to explore it as if it were materially present.

Innovative Digitization in 5 Years

In comparison to the many ongoing digitization projects for cultural heritage sites and endangered collections under international or governmental mandate or museum sponsorship, ARTMYN is a private company. Starting in 2012, they created an ergonomic interface to ‘faithfully capture and represent’ all the characteristic features of an artwork (including color, texture, light, etc.). It was an attempt to challenge people into reevaluating how they experience art. For those of you who have seen the movie, “Loving Vincent,” you likely already have a good understanding of this premise for art viewership. Founded in 2016, ARTMYN developed out of an optical design research project, eFacsimile, under the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology at Lausanne, from a Google Focused Research award. By 2017, they formed an exclusive collaboration with Sotheby’s auction house to create interactive visualizations for select highlights in their seasonal sale.

Shortly after opening, inquiries started coming from specialists, dealers, museums, insurers, and restoration artists. ARTMYN’s new visualization tool, for authenticating and marketing unique works of art, became available to the market and they wanted to relay this information to the public with greater veracity than could be accomplished with a hand-magnifier and a photo-glossy. In 2 years, their list of partners has expanded to include artists, cultural institutions, private organizations and collectors. ARTMYN has been awarded a feasibility grant from the Commission for Technology and Innovation and won the IMD Business School Startup Competition. Although they seek to make the process widely available, currently, the process is expensive, time consuming, and only focuses on one work at a time.

Rendering 3-Dimensional Matter onto 2-Dimensional Space

ARTMYN uses a proprietary, portable scanner to collect tens of thousands of pictures with different light sources from every conceivable perspective and at varying magnitudes of scope. Anything material is made up of matter that is arranged into a certain form. An object’s properties are determined by their particular arrangement of different types of particles, which can be measured by ARTMYN’s technology. The source for how an object is experienced is beyond our sensory limitations but is also required to be certain of an object’s context. Outside of a lab, collection professionals are unable to distinguish the composition of these objects with complete certainty. Different types of prints, in different contexts, can appear very similar. This is also the case with paints, ceramics, woods, resins, etc. Connoisseurs are experienced in looking for context clues that help in these distinctions. ARTMYN will render these skills less needed as this technology will allow anyone to access the same information.

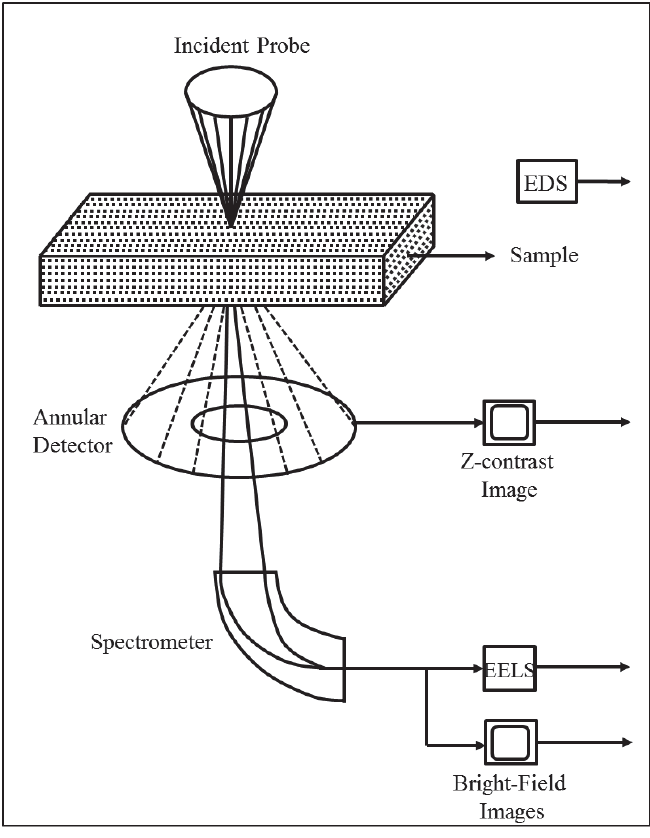

Figure 2. 6. Schematic of Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (STEM). 95

ARTMYN bombards an object with charged light that bounces back at a certain frequency. The energy range is fed through sensors and processed with a computing algorithm into a multidimensional digital visualization. This provides an unwavering explanation as to how and why an object appears the way that it does. All the digital images are merged to create a topographical map of the object and hosted on a network drive or web server.

Source: Khanal, Subarna Raj. "Advanced Electron Microscopy Characterization of Multimetallic Nanoparticles." ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. 2014.

Ownership in Engagement with Open Design

While intended for collectors and collections managers, a digital representation of the scanned object can be interpreted through any computing device and then manipulated by any user with a cursor or touchscreen. As the viewer drills-down and pans-through the map, a re-lit object plane is created. Instead of forcing the same image into a visual that is specific to the viewer’s search parameters, the best-fitting image from the mapping network is retrieved and displayed according to those same requirements. This experience is coded to be useable on any device with an internet connection, regardless of software, if it has the significant processing power required for the visualization stream.

This literal and figurative difference in scope is what distinguishes ARTMYN from other digitization initiatives. Nonprofits often deal in larger structures and collections that are displayed for relatively short periods of time. Derelict structures in ravaging environments, rotting documents in archives, and underutilized artifacts with exhibiting restrictions are all digitized for a museum’s mission of preservation, accessibility, and community development.

Instead of digitizing everything in the collection, ARTMYN digitizes everything about an individual object. With increased usage, more objects will be fully mapped to detail craft marks (ex. painting brushstrokes) that may distinguish an original from a fake and potentially discover works once thought lost. Providing a means to perceive everything that encompasses the individual object, deepens the engagement between the object and its respective viewer, all while preserving its perfection, making these resources obtainable, and educating the audience. However, part of the impetus of scrutiny comes with the advent of 3D printing technology. Apart from being able to create licensed duplicates, for safety when handling displays, or editioned copies, for resale, forgeries are becoming more sophisticated, making it easier to pawn something as its visibly similar equivalent. With the widening disparity of understanding of art and provenance, ARTMYN is charting a better path to in the marketplace.

Realizing art market concerns for reliable attribution, authentication, and condition reporting, ARTMYN found a way for these professionals to get closer to these objects and understand them more fully. While largely profit-driven, this sophistication of digitization raises the standards for objective cataloging and provides potential for more ethical business and more accurate attribution. ARTMYN has the potential to give anyone the analytical tools to become a professional but this access will likely remain limited to a select few and resigned to smaller collections. Different users get different utility from using this product, influencing their willingness to spend the time and labor required to digitize an individual object with ARTMYN’s scanner. The material expense of this equipment prohibits easy replication. It is also expected that this research will be protected to ensure recovery to those who initially invested in the project. While unlikely, it is not impossible to imagine some collectors will be motivated by the spirit of stewardship and making some digital files accessible to the public. Nonetheless, what is offered in nuance to art appreciation is seemingly endless, where what few objects are freely available can be explored for a lifetime of learning.

Resources:

-- “ARTMYN Partnership Brings Art to Life”. Sotheby’s. January 26, 2017. Accessed February 26, 2018. http://www.sothebys.com/en/news-video/blogs/all-blogs/sotheby-s-at-large/2017/01/artmyn-partnership-brings-art-life.html.

-- “Collection”. Van Gogh Museum. 2018. Accessed March 20, 2018. https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/search/collection?q=&artist=Vincent+van+Gogh#s0019V1962.

-- “eFacsimile”. November 28, 2017. Accessed February 26, 2018. Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Lausanne. http://lcav.epfl.ch/research/eFacsimile.

Evnine, Simon J. “Making Objects & Events”. Oxford University Press. 2016.

-- “Fayoum Mummy Portrait”. ARTMYN. Foundation Martin Bodmer. Accessed February 26, 2018. https://www.artmyn.com/partners/fondation-bodmer/OldEgypt_Fayoum/.

Fredericks, Jana. “Rome Wasn't Built in a Day (Because They Didn't Have 3D Printers)”. Arts Management & Technology Laboratory. October 2, 2017. Accessed March 30, 2018. http://amt-lab.org/blog/2017/9/rome-wasnt-built-in-a-day.

Fultz, B. and James M. Howe. Transmission Electron Microscopy and Diffractometry of Materials. 3rd Ed. New York; Berlin; Springer, 2008. Pgs. 517-609.

Fultz, B. and James M. Howe. Transmission Electron Microscopy and Diffractometry of Materials. 4th ed. Heidelberg; New York; Springer, 2013. Pgs. 1-57.

-- "How to Use ARTMYN: A One-Minute Guide". Sotheby’s. Artists Rights Society. Accessed February 26, 2018. http://www.sothebys.com/en/news-video/videos/2017/how-to-use-artmyn-a-one-minute-guide.html.

-- “IMD Executive MBA completes 20th Expedition to Silicon Valley”. International Institute for Management Development. September 2016. Accessed February 26, 2018. https://www.imd.org/news/updates/imd-executive-mba-completes-20th-expedition-to-silicon-valley/.

-- “Innosuisse replaces CTI: Funding opportunities for Swiss researchers, SMEs and industry”. Accelopment. February 15, 2018. Accessed February 26, 2018. http://www.accelopment.com/blog/innosuisse-replaces-cti-funding-opportunities-for-swiss-researchers-smes-and-industry.

Khanal, Subarna Raj. "Advanced Electron Microscopy Characterization of Multimetallic Nanoparticles." ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. 2014.

Lin, Kate. “Museum Data and What to Do With It: Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh”. Arts Management & Technology Laboratory. April 13, 2016. Accessed March 20, 2018. http://amt-lab.org/blog/2016/3/museum-data-and-what-to-do-with-it-carnegie-museum-of-art?rq=Art%20Tracks.

Liu, Lanying. "Application of Digitization in Innovation and Preservation of Religious Art." Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience 13, no. 11. 2016. pgs. 7922-7925.

-- “Redefining the Way We Experience Art”. Sotheby’s. Artists Rights Society. 2017. Accessed February 26, 2018. http://www.sothebys.com/en/news-video/videos/2017/redefining-the-way-we-experience-art.html.

Schwab, Pierre-Nicholas. “Virtual Reality: Interview of ArtMyn founder, Loic Baboulaz”. IntoTheMinds. March 27, 2017. Accessed March 21, 2018. http://www.intotheminds.com/blog/en/virtual-reality-interview-of-artmyn-founder-loic-baboulaz/.

Scott, AR. "ARTMYN Smart Art." Nature 545, no. 7654 (2017): S12-S12.

-- “Sotheby's and ARTMYN Partner on Digital Pilot Project in 2017”. Close-Up Media, Inc. 2017.

Taggart, Emma. “The National Gallery of Art Releases Over 45,000 Digitized Works of Art as Free Downloads”. My Modern Met. December 24, 2017. Accessed March 20, 2018. https://mymodernmet.com/free-images-national-gallery-of-art/.

-- “Technology”. Loving Vincent. 2018. Accessed March 20, 2018. http://lovingvincent.com/technology,48,pl.html.

-- “The Swiss Venture Capital Report 2017”. 3wVentures. Startupticker. http://www.3wventures.com/swiss-venture-capital-report-2017. Pg. 37.

Thanikachalam, N., Baboulaz, L., Firmenich, D., Süsstrunk, S., and Vetterli, M., "Handheld Reflectance Acquisition of Paintings," in IEEE Transactions on Computational Imaging, vol. 3, no. 4. December 2017. pp. 580-591.