By Nick Helms

Colonialism has consistently been a force in the global purview, including the technological space. Historically, colonialism has referred to “the practice of domination over a people and its culture and the appropriation of its wealth, labour, and natural environment” (Muldoon, 2023). While this practice often included the seizure of land and the extension of power, it is now revealing itself in a new domain - technology. The term “digital colonialism” refers broadly to the ways in which technological tools are used as a means of collecting information, all in the interest of power. In recent years, the expansion of artificial intelligence has vastly increased corporations’ global influence. As the world’s technologies continue to advance and innovate, individuals must keep a watchful eye on the ways in which digital colonialism might repeat harmful practices from the past.

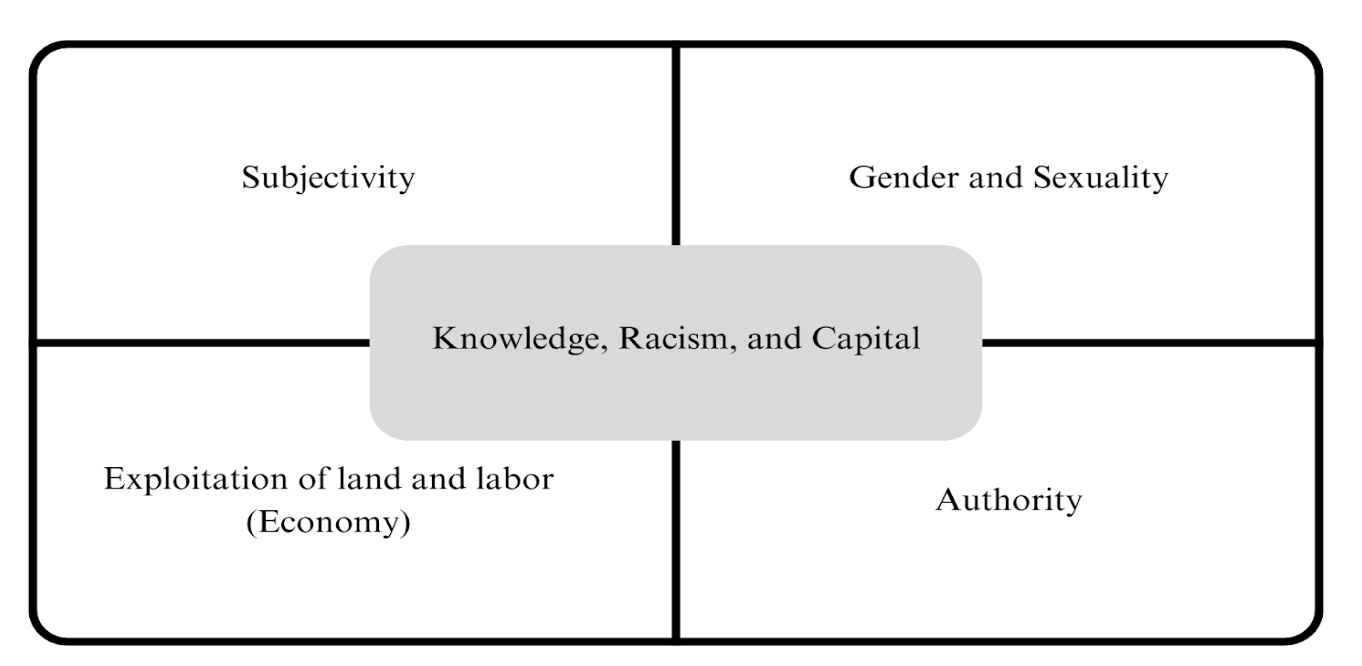

In analyzing the current state of technological practice, it becomes important to consider the structures of colonialism in the digital space. Western corporations, particularly those in the United States, have used their economic and political influence to control significant factors in world economies. Quijano recognizes a “colonial matrix of power [as] an organising principle involving exploitation and domination across four interrelated domains,” depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Quijano’s colonial matrix of power.

Source: Quijano, 2024

All of these domains pertain to the central theme of how so-called “Big Data” has asserted its worldwide dominance and control. The realm of AI includes “both material harms manifested through the deployment of AI technologies and the discursive harms perpetuated by the imaginaries of AI developers and the broader AI industry” (Muldoon, 2023). Each level of harm shows up on the colonial matrix of power and constitutes a unique area of global influence. Beyond the dominant forces at play in digital colonialism, factors of bias can also complicate the situation.

Racial and gender biases in technologies have extended colonialist practices, seen globally as AI continues to expand rapidly. Hammer and Park write that “the invention and salience of modern ideas of race cannot be disentangled from the historical and global processes of colonialism” (Hammar, 2021). The digital space has demonstrated considerable bias, particularly through the democratization of AI programming, which has resulted in explicit racism and sexism becoming engrained in many AI platforms. In 2020, a United Nations reporter found that digital technologies often exponentially increase and entangle the inequities already present in the world (Adams, 2021). Globally, this complicates the power dynamic of Big Data inserting technologies into less developed countries. Particularly in the Global South, this becomes a compounded effort to uphold systemic racism and sexism, all relating back to the tenets of control. However, the colonialist use of technology is not relegated to the Global South; one example is Inuit communities in the Arctic regions, which have seen an influx of technological advances, disrupting centuries of tradition (Young, 2019). The bias seen worldwide extends to the digital sphere and begs the question of who technology ultimately serves.

Beyond the biases it upholds, digital colonialism implements a commodification of the human experience and a geopolitical race toward technological domination. The reduction of humans to a series of data points makes people seem like mere cogs in the wheel of a global marketplace. Big Data has always been about improving bottom lines and being the first to capitalize on a new market (or pushing competition out of an existing market). In the larger context of competitive world economies, many countries are rapidly investing in the advancement of technologies for these same reasons (Adams, 2021). Especially with artificial intelligence, the potential to reimagine current ways of life is enormous, not to mention wildly unregulated. Couldry and Mejias observe that “the corporate ambitions of data industries are always global, just as capitalism and colonialism are global, and the framing of those ambitions appeals to a mandate that pretends to address problems for the whole of humanity” (Couldry, 2023). Guised under a veil of charity, the real intent of technological interference is actually quite malicious. Big Data wants to collect user data for means of surveillance and power, all stemming back to its capitalist and colonialist influences. Under this worldview, a new subset of digital colonialism emerges — the field of data colonialism.

Data has become the underlying motivator for big corporations to enter new world economies, as it presents an opportunity for expansion and control. It mirrors the ways in which historical colonialism aimed to steal and occupy land. As a new frontier for advancement, data collection represents only the first step of technological manipulation (Mejias, 2024). The Global South has seen many of the biggest tech corporations rapidly intensify attempts to infiltrate the market. Their reasons for doing so are numerous: surveillance, control of intellectual property, influence in the flow of information, social monitoring, data commodification, and more (Kwet, 2019). The opportunity to essentially spy on users and collect their data has major advantages for corporations, particularly in the context of capitalist marketplaces. It also enables governmental bodies, regardless of structure, to collect information on its people, which could be weaponized. In the current age of digital misinformation, this becomes all the more dangerous.

Agency and choice have been rapidly diminishing as a result of the colonialist nature of technologies. One notably frightening example of the eradication of choice took place in early 2021 and dramatically affected users in the Global South. Facebook acquired WhatsApp in 2016 and originally let users retain some control over what data was shared with Facebook. However, starting in 2021, WhatsApp stopped letting users opt out, almost undoubtedly due to the fact that they knew many of their global customers had no alternative options for communication (Nothias, 2023). This creates an illusion of choice in which companies present options that contain no real substance. From a larger political context, Mouton and Burns write that “this new(er) form of imperialism presents itself as a service that individuals can ‘opt-out’ of, thus echoing neoliberal conceptualizations of individuals as subjects of human capital” (Mouton, 2021). Further complications arise when ethical questions are introduced. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many questions sprung up about whether or not governments could obtain and use data in the interest of public health. While perhaps used for good to combat the pandemic, this could be a slippery slope toward an ethical decay. A current example is the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s tracking of undocumented immigrants’ data, which can be used to fastrack measures of deportation (Ávila, 2024). Therefore, the question remains - to oppose the misuse of data, how do global citizens stand up and take action?

TAKING ACTION

Many courses of action have been proposed to counteract Big Data’s unethical systems of control. Perhaps most obvious is the introduction of data protection laws to establish oversight and regulation for the benefit of consumers. A key example of this is the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), a comprehensive law intended to give individuals greater control over the collection and storage of their personal data. However, as technologies continue to evolve, policies’ shortcomings begin to reveal themselves, as has been the case with GDPR which has not provided much in terms of combating unethical AI usage (Coleman, 2019). Additionally, while noble in their desired outcomes, GDPR and other data protection laws often have difficult implementation strategies, particularly in global markets where technological rules often differ. Policy might be a start for returning power to consumers, but it has thus far proven to not be the only solution.

Others have advocated for more holistic and people-centered approaches to remediating systems of digital colonialism. One such practice is digital retooling, which “refers to a convergence of practice-based methods and critical research through which [one recalibrates their] digital artistic practice at both the front and backend to create original artistic interventions, frameworks, and projects” (Kawash, 2022). This approach is rooted in ethics of care and emphasizes the need for individuals to have agency and liberated choice. In doing so, it restores power to the people and revokes corporations’ ability to collect data from its users. Another widely-recognized approach is to apply organizing principles from activists to the digital space. To regulate Big Data, this method requires three inputs: a shared sense of language to combat global issues, the capture of public opinion to gauge consumers’ desires, and a transnational system of organizing across race and class (Nothias, 2023). By engaging these principles, individuals can rise up and challenge Big Tech’s systems of maintaining control.

In conclusion, the digital world has promoted an agenda eerily reminiscent of historical colonialism, but the data collection practices of the present need not transfer to the future. The rise of large tech corporations has led to a global reckoning where technology seizes control of people’s data in a manner similar to historical land acquisition. User rights are diminished by data collection policies, which sustain surveillance and information tracking. To combat these measures, a global majority must unite and identify strategies to maintain individual control. Alongside worldwide oversight in the form of policy, this may reduce the potential harms of Big Data’s rapid spread. In the quest for technological advancement, ethical concerns about individual rights must remain at the forefront of global discussion to avoid a repetition of historical wrongs.

-

Adams, Rachel. “Can Artificial Intelligence Be Decolonized?” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 46, no. 1–2 (March 1, 2021): 176–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/03080188.2020.1840225.

Ávila. Renata, and Saša Savanović. “Digital Colonialism and Covid-19.” New York and London: OR Books, 2021. Accessed September 29, 2024. ProQuest Ebook Central. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cm/reader.action?pq-origsite=primo&ppg=93&docID=6519978.

Coleman, Danielle. “Digital Colonialism: The 21st Century Scramble for Africa through the Extraction and Control of User Data and the Limitations of Data Protection Laws.” Michigan Journal of Race & Law, no. 24.2 (2019): 417. https://doi.org/10.36643/mjrl.24.2.digital.

Couldry, Nick, and Ulises Ali Mejias. “The Decolonial Turn in Data and Technology Research: What Is at Stake and Where Is It Heading?” Information, Communication & Society 26, no. 4 (March 12, 2023): 786–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1986102.

Hammer, Ricarda, and Tina M. Park. “The Ghost in the Algorithm: Racial Colonial Capitalism and the Digital Age.” In Global Historical Sociology of Race and Racism, edited by Alexandre I.R. White and Katrina Quisumbing King, 38:221–49. Political Power and Social Theory. Emerald Publishing Limited, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0198-871920210000038011.

Kawash, Ameera. "Digital Aftercares: Digital Retooling for Agency, Value, and Co-Vulnerability as Artistic Practice." Order No. 30259793, Royal College of Art (United Kingdom), 2022. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/digital-aftercares-retooling-agency-value-co/docview/2778644812/se-2.

Kwet, Michael. “Digital Colonialism: US Empire and the New Imperialism in the Global South.” Race and Class 60, no. 4 (2019): 3-26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396818823172.

Mejias, Ulises A. and Couldry, Nick. Data Grab: The New Colonialism of Big Tech and How to Fight Back. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2024. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226832319.

Mouton, Morgan, and Ryan Burns. “(Digital) Neo-Colonialism in the Smart City.” Regional Studies 55, no. 12 (December 2, 2021): 1890–1901. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1915974.

Muldoon, James, and Boxi A. Wu. “Artificial Intelligence in the Colonial Matrix of Power.” Philosophy & Technology 36, no. 4 (December 15, 2023): 80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-023-00687-8.

Nothias, Toussaint. “How to Fight Digital Colonialism.” In Imagining Global Futures, edited by Getachew, Adom. Cambridge, MA: Boston Review/Boston Critic Inc, 2023.

Quijano, Aníbal, Mignolo, Walter D., Segato, Rita and Walsh, Catherine E. Aníbal Quijano: Foundational Essays on the Coloniality of Power. New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478059356.

Young, Jason C. “The New Knowledge Politics of Digital Colonialism.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 51, no. 7 (October 1, 2019): 1424–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19858998.