Written by Clara Perez Alfaro, John McAllister, Ashley Jones, Amarachi Ekekwe, Marina Cavalcanti

This study analyzes the current state of diversity and inclusion of Black, Indigenous, (and) People of Color within film festivals in Europe, the United States, and Canada. Assumptions behind the research are that with meaningful change implemented to increase racial diversity in festivals’ programming staff there will be a selection of more diverse film directors. This report consists of parts:

Interviews focused on filmmakers and film festival programmers. These are used to reveal common trends from personal experiences regarding diversity within film festivals

Analysis of a survey of film festival attendees conducted to understand their perceptions of diversity and inclusion in festivals’ lineup and programming staff

The full report will be available soon in Reports and includes greater depth of analysis of each of the above sections and a third analysis of a case study of the current state of representation at the International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR).

Film festivals are an essential part of the movie industry, as they provide opportunities for creators to garner recognition and to secure distribution for their films. However, there is a lack of racial representation and inclusion in the entertainment industry that prevents filmmakers of color from having the same opportunities as their White counterparts. The Programmers of Color Collective (POC2) was founded in 2019 to address the lack of representation in film festival programmers, the individuals that are responsible for the selection of films (Obenson, 2019). The Collective actively tackles this issue by conducting studies on the composition of film festivals, creating mentorship programs, and advocating for more BIPOC programmers to be hired. This study was conducted in collaboration with POC2.

CONTEXT

The globalization of the film industry has increased the exportation of movies, allowing worldwide audiences to see stories that represent voices and realities that differ from their own. With this increased globalization, films have an immense platform to showcase a plurality of voices and promote social change. However, the film industry has failed to achieve racial equality, as it remains a predominantly White industry (Dargis, et. al., 2016).

The resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 came with some efforts from the film and entertainment industry to showcase Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) creators and artists. Netflix amplified Black narratives through their Strong Black Lead campaign (Ibrahim, 2020). Likewise, although it was deemed not as progressive by some activists, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences set forth diversity and inclusion rules to encourage representation on and off-screen (Romo, 2020). However, despite these strides to improve diversity, BIPOC still fail to see themselves represented in mainstream media (Moore, 2020).

Film festivals are an instrumental part of the industry, as they are a signaling point when it comes to uncovering talent and setting industry standards (Rosser, 2021). Therefore, festivals have the responsibility to showcase a plurality of voices and ensure that racial inclusion is the standard. Festival programmers, those responsible for selecting films and curating the lineup, shape the tone of the festival and play a crucial role in deciding which voices to showcase and elevate.

Independent filmmakers rely on film festivals as they provide exhibition, recognition, and distribution opportunities (Rastegar, 2012). However, due to systemic racism, BIPOC filmmakers have fewer opportunities in the industry, shown by the large discrepancy between the number of White vs BIPOC directors accepted to festivals. Of the 325 films accepted to the five major film festivals (Cannes, Berlin, Sundance, Venice, and Toronto) between 2017 and 2019, only 35% were directed by people of color (Smith, 2020). Similarly, BIPOC filmmakers directed only 38% of the films featured at the top ten North American festivals over the past three years (Smith, 2020).

Furthermore, festivals are usually hesitant to disclose those numbers and often mask them by lumping different underrepresented groups into a single statistic to appear more diverse. For example, the 2021 Tribeca Festival announced that over 60% of their program’s feature films were directed by females, BIPOC, and LGBTQ+ filmmakers (Tribeca Festival, 2021). This is only dilutes each group’s actual numbers, making the total seem better than what it might be, but it also fails to recognize BIPOC specific struggles by including them in the same group as white, cisgender women.

Although a myriad of factors could explain the low ratio of BIPOC to White directors accepted to festivals, the racial make-up of the programming team is key, as it is mirrored by the racial make-up of the directorial pool. Programmers are responsible for curating the films selected for film festivals. Only 26% of programmers at the top ten North American film festivals are BIPOC. The proportion is even lower for the top five international film festivals, with only 21% of programmers identifying as BIPOC (Smith, 2020). The underrepresentation of BIPOC at the curatorial and directorial level perpetuates the systems of inequality in the film industry.

Additionally, festivals often invite programmers to take part in the selection committees without compensation (POC2, personal communication, April 2021). This practice also perpetuates systems of inequality by making opportunities available only to those that already have the financial condition to accept low or unpaid positions, which tends to be White individuals (Bhutta, et. al, 2020). BIPOC programmers are often the ones not able to accept these unpaid roles, which shuts them out of opportunities that could advance their careers and allows only the same privileged programmers to be promoted.

Even when included, in a festival’s staff, programmers of color endure prejudices and biases. In a letter to the British Film Institute (BFI) London Film Festival, programmer Jemma Desai detailed the circumstances that led to her resignation, noting that the festival leadership had established a clear message about the value that [they] place on [her] perspectives and how [they] want to utilize them through a tokenistic invitation to sit on an interview panel where [her] views were dismissed and where racialized and deeply flawed judgments were made about candidates” (Desai, 2020, para. 7).

Similarly, in her resignation letter to the Images Film Festival, programmer Sarah-Tai Black recalled a situation in which Directors were hesitant to program work from and of BIPOC artists without even examining the work or having any knowledge of the relatively well-known suggested artists (Black, 2019). This situation then “[set] the tone for eight months in which [her] opinions, contributions, and intuitions [were] devalued and ignored, despite clear evidence that [she is] more than capable as a programmer, curator, and coordinator” (Black, 2019, para. 10).

These incidents are not isolated, and they represent the discriminatory practices experienced by programmers of color. As key players in the industry, film festivals have an immense platform to speak up on these issues and elevate the voices of people of color.

INTERVIEWS

Key informant interviews were vital to understanding the experiences of BIPOC at film festivals. To make the interviews as valuable as possible, the questions were tailored to each interviewee’s background and experience. Twelve interviews were conducted with a preliminary questionnaire for each interviewee to collect demographic data. Of these 12 informants, five identified as film directors, five as festival programmers, and two as a combination of both. Six interviewees identified as women, four as men, one as a trans-man, and one chose not to identify. As it pertains to race/ethnicity, eight respondents identified as African American/Black, two as Latinx, one as Bi-Racial, and one as Albanian. The interviewees represented 35 film festivals over four continents, including the Durban International Film Festival, the Toronto International Film Festival, the Afrikkana Film Festival, and the Philadelphia Film Festival.

Personal Experiences

The varying levels of experiences between programmers and directors were key, as most interviewees described experiences that were similar at their core: they were all silenced due to preconceived notions of BIPOC festival programmers and film directors.

A common concern between interviewed programmers and directors was the feeling of tokenism, being treated as the spokespeople and representatives of their race. Of the 12 interviewees, 10 recounted experiences where they were the only ones of their race or ethnicity in the room. Thus, their opinions were either ignored or taken as indicative of the opinions of everyone who is of the same race or ethnicity. who provides a Black perspective in these rooms. One programmer said that she is “the only person I feel like I fulfill their quota” (personal communication, January 19, 2021). Another programmer said: “The change will come from changing the board and the jurors; they are the ones selecting films, the ones giving awards, and the ones considering they are not represented. How can we change if we only have one perspective represented? The ones who do not represent the majority feel lonely” (personal communication, January 20, 2021).

The sentiment about diversity often being treated as a box to check is supported by an open letter signed by 5,000 Black & Brown creatives which called for “strategic commitments” from entertainment gatekeepers to make the festival industry more racially equitable in the U.K. This letter states that “only 5% of the producers supported by the British Film Institute in 2018/2019 were producers of color” (Ravindran, 2020, para. 5). When a population is not adequately and fairly represented, it creates a system that continues to perpetuate racism.

Another thread among the interviewed filmmakers was that, as BIPOC directors, they are hindered from applying to festivals due to costs. As a film director, S-hekh Shem Hetep mentioned, “going to a film festival is a privilege because you have to have disposable income” (personal communication, January 6, 2020). A 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances shows that “the typical White family has eight times the wealth of the typical Black family and five times the wealth of the typical Hispanic family” (Bhutta, et. al, 2020, para. 1). This large income gap extends to all areas, including having the ability to afford to apply and attend festivals.

Although applying to one or two festivals is not as expensive, it can become costly when applying to multiple festivals at a time. Figure 1 shows that of the top five film festivals in 2019, application fees can be as high as $500 as is the case for the Tribeca Film Festival (Wilkins, 2020). If a filmmaker is not granted a fee waiver, they could potentially spend thousands of dollars. Although all filmmakers must incur these costs, due to systemic racism, BIPOC individuals tend to have less disposable income, causing a more significant financial impact if a submitted film does not get selected. (SEE FIGURE 1)

Figure 1: Top 5 Film Festival Entry Fees in $USD (2019).

Note: Adapted from “The Top Film Festivals Worth the Entry Fee in 2021,” by H.Wilkins, 2020. Copyright 2021 by StudioBinder Inc.

Diversity and Inclusion

Diversity means something different in each country that was represented through the interviews. In Africa, for example, the content produced and featured is mostly Black, but festival lineups do not always reflect the myriad of voices present in the continent’s communities. One filmmaker said that “diversity in Africa isn’t about race but sexuality. There needs to be African queer content” (Filmmaker, personal communication, January 27, 2021). Diversity is about visibility and representation of all identities.

According to a festival programmer, the word diversity is flawed, as “it has become the term people use to look better; diversity doesn’t work, inclusion does” (Programmer, personal communication, 2021). This sentiment was shared by Jemma Desai in her resignation letter to BFI London, where she spoke about the lack of resources inclusivity programs were given, making these seem like token efforts (Desai, POC2 archives, 2020). Likewise, more than half of the interviewees spoke about the lack of support they experience from the festival organizations; they are not given positions of leadership and oftentimes are underpaid or not paid at all.

SURVEY

An online survey was conducted targeting film industry professionals that have attended festivals in the U.S., Canada, and/or Europe. The survey was developed through the Qualtrics platform and distributed via the Programmers of Colour Collective’s network from January 26 through March 31, 2021. Additionally, specific festivals were targeted within our geographical scope, as well as industry-related Facebook and LinkedIn groups to expand the pool of respondents.

Given the survey’s niche target audience, it was challenging to reach respondents that fulfilled all of the requirements, primarily attendance at a film festival in the target regions. Therefore, only 89 of the total 177 responses were accounted for in the analysis. Moreover, some partial responses were considered as they provide valuable data for analysis.

The majority (71.9%) of respondents identified as female, while 25.8% identified as male and the remaining 2.2% as Non-binary / Third gender. In terms of age, respondents skewed towards the younger demographic, with 53.9% falling within the 18-34 age range. As the age range decreases, the number of respondents increases. As for race/ethnicity, the survey reached an almost equal number of BIPOC and Non-BIPOC respondents, with the former making up 54% of the respondent pool. However, the results between BIPOC and Non-BIPOC overlap, since respondents could select multiple races and/or ethnicities. In examining individuals’ roles in film festivals, 49.4%attended festivals as Programmers, while the rest varied between Festival Operations,Publicity/Marketing, Film Distribution, etc. . Among those who identified as Festival Programmers, 56% self-identified with at least one race/ethnicity within the BIPOC definition

The survey analysis garnered insights with four main focuses: diversity in storytelling; disparities in responses between younger and older age groups; variation in responses between BIPOC and Non-BIPOC respondents; and specific responses from programmers of color.

Diversity in Storytelling

When analyzing the factors for choosing what films to watch at a festival, the storyline of the film was the most important (see Appendix E, Figure E5). Although diversity in cast and diversity in creators (4th and 7th in respondents’ priorities, respectively) are also fundamental in the industry, this data highlights how important it is for inclusion to be achieved through representative storytelling that resonates with the audience being reflected. Addressing diversity in storytelling not only contributes to diverse audiences feeling authentically represented on screen but also ensures that audiences, in general, are exposed to diverse stories that differ from their realities.

Younger vs. Older Respondents

Younger and older respondents differed significantly in how much value they give to diversity and how they perceive it within the film festival industry. When looking at the most important factors for choosing what films to watch at festivals, at least some aspect of diversity (of cast or creators) was a consideration for most age groups, except for those ages 65-74, as shown in Figure 2. Additionally, diversity was higher in priority than recognition/star power of the people involved for almost all age groups.

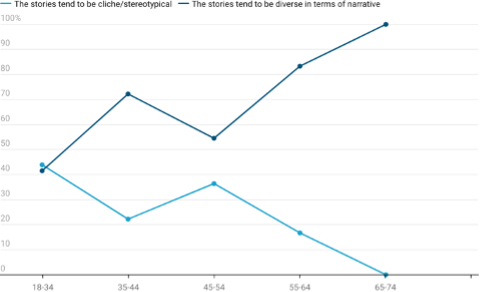

The fact that older respondents seemed to not pay as much attention to diversity might be closely associated with an overall positive perception from this group towards diversity in the industry. For example, when prompted about BIPOC filmmakers selected for festivals, older respondents tended to perceive their films as diverse, while younger demographics saw them as stereotypical or cliché. Furthermore, as the age of the respondents increased, the percentage of individuals that find those stories stereotypical generally decreased, as shown in Figure 3. Conversely, the proportion of those that find the stories diverse in terms of narrative generally increased with age.

Figure 2: Most Important Factors in Film Selection, By Age.

Note: Derived from Question 13: At film festivals, which two factors are the most important when choosing what films to watch.

Figure 3: Opinions on Films Selected by BIPOC Filmmakers, By Age

Note: Derived from Question 17: Which of these options best represent your opinion on the films by BIPOC filmmakers that are usually selected at film festivals?

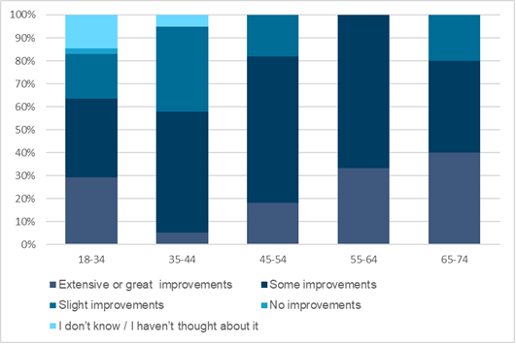

With regards to the improvements made to the racial and ethnic diversity of filmmakers selected at festivals, opinions were varied, but the predominant sentiment among most age groups was that some improvements have been made in this area, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Opinion on Improvements to Racial and Ethnic Diversity of Directors Selected.

Note: Derived from Question 15: Looking specifically at BIPOC directors, do you think film festivals have had improvements in terms of the racial and ethnic diversity of the directors selected over the past 5 years?

Although there was not an explicit disparity between the opinions of older and younger respondents regarding the state of these improvements, there was a clear difference when it came to the satisfaction levels towards these improvements. As shown in Figure 5, older respondents were more satisfied, as dissatisfaction levels decreased drastically for respondents over 55 years of age. The findings show that younger individuals are generally more skeptical and critical about the lack of diversity in the industry and tend to be the ones dissatisfied and demanding more change compared to older individuals.

Figure 5: Satisfaction Levels Regarding the Improvements to Racial and Ethnic Diversity of Directors Selected

Note: Derived from Question 16: How would you rate your satisfaction level regarding these improvements in the diversity of the directors selected at film festivals over the last 5 years?

BIPOC vs. Non-BIPOC Respondents

BIPOC and Non-BIPOC respondents showed significant differences in their perceptions of diversity at film festivals. In terms of the most important factors for selecting a film, 64% of respondents that prioritized diversity of the cast was BIPOC. Likewise, 67% of respondents that prioritized the diversity of creators were BIPOC, making these two options two the most selected choices for BIPOC respondents and the least selected for non-BIPOC. Additionally, when looking at the diversity of filmmakers, 43% of BIPOC respondents felt that the directors selected are “a little” or “not diverse at all” compared to 26% of non-BIPOC respondents. Non-BIPOC respondents showed less prioritization when it comes to diversity in films and a slightly more positive view on the diversity of directors, which may indicate an overly optimistic view about the current state of diversity and inclusion in the industry

With regards to improvements towards diversifying directors, BIPOC responded less favorably than non-BIPOC. While 45% of BIPOC and 48% of non-BIPOC felt there have been “some improvements”, 33% of non-BIPOC felt there have been “great or extensive improvements”, compared to only 17% of BIPOC (see Appendix E, Figure E8). Satisfaction levels surrounding these improvements were similar between the two groups; 55% of BIPOC respondents and 45% of non-BIPOC displayed some level of dissatisfaction (see Appendix E, Figure E9). These responses could indicate that while there have been slight improvements in diversity, it does not mean that there is inclusion, which suggests the need for change. One respondent expanded on their answer: “Inclusivity and diversity have become buzz terms; however, the improvements are barely there. For example, there are more events about BIPOC voices or diversity, but there are rarely BIPOC voices in events/workshops that do not center race. In other words, BIPOC can only talk about race and racism” (Survey Respondent, personal communication, 2021).

The survey also examined how individuals saw the opportunities given to BIPOC filmmakers compared to their White counterparts. When looking at the differences between the budgets of films by BIPOC and non-BIPOC directors, 48% of non-BIPOC respondents selected that they “didn’t know or haven’t thought about it”, compared to only 25% of BIPOC. Additionally, 63% of BIPOC respondents selected that “films by BIPOC are made with significantly smaller budgets”, compared to 45% non-BIPOC.

This may indicate a lack of awareness of these issues by non-BIPOC respondents. If White individuals, the current decision-makers, are not considering how to institute change on the accessibility level, the system will continue to permeate systemic racism.

BIPOC Programmers

There was a fairly even racial and ethnic distribution among programmer respondents, with 53% identifying as BIPOC and 47% as non-BIPOC. The overall perception of diversity among programming teams was fairly neutral with respondents split between “somewhat diverse” and “a little diverse” and a majority believing there have been “some improvements” to the diversity of programmers over the past five years. A large portion of respondents also selected that “there are opportunities for advancement for BIPOC staff” within film festivals.

While this seems positive, many BIPOC programmers feel that change still needs to happen. One respondent expanded on the lack of advancement opportunities for BIPOC: “Non-POC programmers tend to advance in the industry much quicker. At the intersection of race and class, the low pay of this industry also makes it more difficult for underprivileged people to afford the amount of time it takes to climb the ladder. The lack of opportunities, in general, makes it more common for people to look to their network for hiring, rather than a formal application process, which tends to shut out POC and limit growth opportunities when the status quo ensures this network remains primarily White.” (Survey Respondent 2, personal communication, 2021)

Based on these comments, as well as the aforementioned letter from former and current POC program advisors at the London Film Festival (Desai, 2020), it is clear that while there is some diversity and there are some improvements, there is also a disparity between BIPOC and White programmers. If BIPOC programmers are not able to advance in their careers as quickly as their White counterparts, there is no equity.

CONCLUSION

To promote and reach racial inclusion, film festivals should: (1) Collect data to uncover pain points and set clear measurable goals towards diversity; (2) Utilize POC2 as consultants to establish impactful mentorship programs and to improve upon existing ones to specifically address the needs of BIPOC; (3) Invest in programmers of color at each stage of their career to ensure that the profession is sustainable for every participant.

If one wants to find a place where actions are moving in the right direction, Sundance Film Festival received praises for diversifying both their programs and programming board. In 2020, the organization released an official statement denouncing white supremacy and supporting Black Lives Matter. Additionally, the festival reported data on the makeup of their full institute team. BIPOC represented 27.4 % of the staff, 46.2% of the curatorial teams, 22.2% of the executive leadership, and 28.1% of the board of directors (Putnam, 2020). By making their commitments to diversity and inclusion public and being transparent with their data, Sundance is becoming a leader in the entertainment industry, not only by ensuring that multiple BIPOC are in all spaces but also by recognizing their flaws and room for improvement as an organization.

+ Resources

Bhutta, N., Chang, A. C., Detting, L. J., & Hsu, J. W. (2020). Disparities in Wealth by Race and Ethnicity in the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances. Retrieved March 05, 2021, from https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/disparities-in-wealth-by-race- and-ethnicity-in-the-2019-survey-of-consumer-finances-20200928.htm

Black, S. (2019). Resignation Letter to the Images Board. Retrieved from POC2 Archives.

Boerman, T. (2017). Black Rebels: Navigating the Cultural Divide. Retrieved March 2, 2021, from https://iffr.com/en/black-rebels-navigating-the-cultural-divide

Business Wire. (2021). Lena Waithe & Hillman Grad Productions Join Forces with Indeed to Showcase BIPOC Filmmakers through ‘Rising Voices’ Initiative [Press release]. Retrieved March 2, 2021, from https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210216005250/en/Lena-Waithe-Hillman- Grad-Productions-Join-Forces-with-Indeed-to-Showcase-BIPOC-Filmmakers-through- Rising-Voices-Initiative

Crul M., Lelie F., Keskiner E. (2018) The Second and Third Generation in Rotterdam: Increasing Diversity Within Diversity. Scholten P.,

Crul M., van de Laar P. (Eds) Coming to Terms with Superdiversity (pp. 51-71). IMISCOE Research Series. Retrieved May 1, 2021 from https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96041-8_3

Cross, H. (2020). How to Get Tickets for the Tribeca Film Festival. Retrieved May 11, 2021 from https://www.tripsavvy.com/tribeca-film-festival-tips-1613707

Dargis, M., & Scott, A. O. (2016). Hollywood, Separate and Unequal. Retrieved February 5, 2021, from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/18/movies/hollywood-separate-and- unequal.html

Desai, J. (2020). Recommendations & Concerns from the POC Programmers at the London Film Festival. Retrieved from POC2 Archives.

De Valck, M. (2007). Film festivals: From European geopolitics to global cinephilia. Retrieved May 11, 2021 from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Educational outreach programs (2021). Retrieved May 11, 2021 from https://biff1.com/community/educational-outreach/.

Gilmartin, S., Simard, C., & Wullert, K. (2019). The Mistake Companies Make When They Use Data to Plan Diversity Efforts. Retrieved May 11, 2021 from https://hbr.org/2019/04/the- mistake-companies-make-when-they-use-data-to-plan-diversity-efforts

Ibrahim, S. (2020). Netflix's 'Strong Black Lead' Marketing Team Shows the Power (and Business Benefit) of Amplifying Black Voices. Retrieved February 5, 2021, from https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/netflixs-strong-black-lead-marketing-team-shows-power-business-benefit-amplifying-black-voices-1305775

IFFR (2019). New festival director Vanja Kaludjercic. Retrieved March 2, 2021, from https://iffr.com/en/blog/new-iffr-festival-director-vanja-kaludjercic

IFFR (2020). Annual Report 2019-2020. Retrieved March 2, 2021, from https://iffr.com/en/annual-report/2019-2020

IFFR (2021). About CineMart. Retrieved March 2, 2021, from https://iffr.com/en/about-cinemart

IFFR (n.d.). IFFR is... Retrieved March 2, 2021, from https://iffr.com/en/who-we-are

Macnab, G. (2020). Rotterdam Film Festival unveils major changes to programming structure. Retrieved March 2, 2021, from https://www.screendaily.com/news/rotterdam-film-festival-unveils-major-changes-to-programming-structure/5151385.article

Moore, S. (2020). The Importance of Black Cinema and Supporting BIPOC Films. Retrieved February 5, 2021, from http://culture.affinitymagazine.us/the-importance-of-black- cinema-and-supporting-bipoc-films/

Obenson, T. (2019). Inclusive Film Festival Programming Initiative Programmers of Colour Launches at Sundance. Retrieved February 5, 2021 from https://www.indiewire.com/2019/01/poc2-programmers-of-colour-diversity-inclusion- sundance-1202038202/

Patten, D. (2021). Ava DuVernay ON Thursday's launch of array Crew: ON-SET Inclusion, Getting studios & Streamers Onboard & how "this isn't the Yelp of Job SEARCHES". Retrieved May 11, 2021 from https://deadline.com/2021/02/ava-duvernay-array-crew- launch-inclusion-production-studios-peter-roth-netflix-disney-1234696044/

Pieper, K.M., Choueiti, M., Smith, S.L., Ph., D., & Annenberg (2014). Race & Ethnicity in Independent Films: Prevalence of Underrepresented Directors and the Barriers They Face. Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism, USC. Retrieved February 5, 2021, from https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Research-Art-Works-Sundance.pdf

Putnam, K. (2020). Black Lives Matter. Retrieved March 01, 2021 from https://www.sundance.org/blacklivesmatter

Rastegar, R. (2012). The Curatorial Crisis in Independent Films. UCLA: Center for the Study of Women, 6. Retrieved May 11, 2021 from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4mb0f534

Ravindran, M. (2020). U.K.’s Black & Brown Creatives Call for ‘Strategic Commitments’ to Representation in Open Letter Signed by 5,000 (EXCLUSIVE). Retrieved May 11, 2021 from https://variety.com/2020/film/global/open-letter-diversity-inclusion-nisha-parti-meera-syal-anita-rani-1234644010/

Reflecting, Rethinking and Resetting: The Industry in Flux. (2021). Retrieved May 11, 2021 from https://www.efmberlinale.de/media/pdf_word/efm/71_efm/efm2021_reflectingrethinking resetting_reportthinktanks.pdf

Romo, V. (2020). Oscars: Future films must meet diversity and inclusion rules. Retrieved February 5, 2021 from https://www.npr.org/sections/live-updates-protests-for-racial- justice/2020/06/12/876481972/oscars-future-films-must-meet-diversity-and-inclusion-rules

Rosser, M. (2021). Make festivals more accountable for diversity, urges Rotterdam panel. Retrieved March 2, 2021 from https://www.screendaily.com/news/make-festivals-more-accountable-for-diversity-urges-rotterdam-panel/5156883.article

Smith, S. L. (2020). Inclusion at Film Festivals: Examining the Gender and Race/Ethnicity of Narrative Directors from 2017-2019. Time’s Up Foundation & USC Annenberg. Retrieved May 11, 2021 from http://assets.uscannenberg.org/docs/aii-inclusion-film-festivals-20200127.pdf

Tangcay, J. (2021). Ava DuVernay launches ARRAY Crew, Promoting Below-the-Line Diversity. Retrieved March 05, 2021 from https://variety.com/2021/artisans/news/ava- duvernay-array-crew-launch-1234910383/

Tegeltija, S. (2017). Mapping Contemporary Cinema. A Short Guide to International Film Festival Rotterdam. Retrieved March 2, 2021 from http://www.mcc.sllf.qmul.ac.uk/?p=1828.

Time's Up Foundation (n.d.). Retrieved from Who’s in the Room: A Mentorship Program to Help Diversify the Executive and Producer Ranks of the Industry. Retrieved May 11, 2021 from https://timesupfoundation.org/work/times-up-entertainment/whos-in-the-room-a-mentorship-program-to-help-diversify-the-executive-and-producer-ranks-of-the-industry/

Tribeca Festival (2021). 2021 Tribeca Festival Announces Feature Film Lineup Including In- person World Premieres & Special Events. Retrieved May 11, 2021 from https://tribecafilm.com/press-center/festival/press-releases/2021-tribeca-festival- announces-feature-film-lineup-including-in-person-world-premieres-and-special-events

Welk, B. (2020). Sundance Slate Hits 50-50 Mark for Women and Nonwhite Directors. Retrieved May 9, 2021 from https://www.thewrap.com/sundance-film-festival-diversity- half-women-nonwhite-directors/

Wilkins, H. (2020). Top film Festivals worth your time and money. Retrieved March 01, 2021 from https://www.studiobinder.com/blog/top-film-festivals/