In the age of mass production, skilled workers must adapt in order to sustain their role in the textiles industry. In this context, skilled workers can be considered a craftspeople who have a vast knowledge of textile production and textiles-related objects and use the tools available at the time. As machines have become more capable, individuals have had trouble keeping up economically and temporally since these machines can produce textiles in less time, for less money. An understanding of skilled workers’ relationship to technologies in the textile industry can help arts organizations support their work.

Technology in the Textile Industry

The concept of mass production was developed in the late 18th century, introducing into production the ideas of interchangeable parts, division of power, and various machines that helped expedite production. Machines relative to the textiles industry, such as the spinning jenny and the power loom, aided skilled workers with painfully slow tasks such as spinning yarn and weaving. Quickly, however, technology developed further, and skilled workers lost much of the work they had been in charge of before. They became merely operators. Due to these technological developments, skilled textile workers had to adapt their practices in order to sustain themselves while continuing to create within the industry.

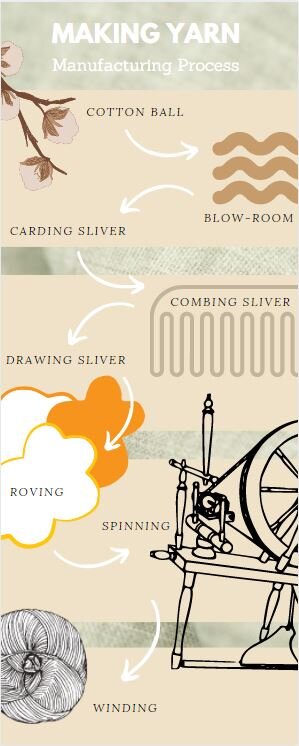

Figure 1: Infographic showing the yarn making process. Source: Author.

Today, the textile artist must adapt depending on the accessibility of machinery—such as laser cutting, knitting machines, or computerized looms. A divide developed within the industry around the time that textile tools became more automated and computerized. This division has created the separated roles of the artist and the machine operator. The artist could decide to be both, rendering their practice more efficient. However, this is an advantage that not all textile artists have as these machines are expensive and oftentimes require experienced hands to operate without damage. For example, a computerized knitting machine price range is anywhere between $10,000-$190,000 according to the Los Angeles Times. On the higher end of that price range, the machines are very reliable and fast. Shima Seiki is a company that sells various kinds of high end computerized knitting machines. This is one of the most top notch manufacturers in its domain. Older used models of lower tier brands can be found on eBay for just under $1,000. However, these are made smaller, not capable of textiles at the level of high end machines.

Artists’ use of Technologies

Artists have had to adapt to the changing work ecosystem by taking advantage of the technology available in their organizations if they attend schools or work for companies with such technology. If the artist has access to a computerized loom or knitting machine, they could save energy and channel it all into coming up with the ideas and transferring them into coded versions of the product they’d like to make. This way, they could produce more prototypes without spending a lot of time worrying about the technical aspects, only to realize in the end that they are not quite satisfied with the final product.

Figure 2: A Shima Seiki knitting machine. Source: Shima Seiki.

For those who do not have computerized machinery lying around, there has been another adaptation veering more towards a DIY approach: using existing textiles. Specifically, in the world of clothing design, there has been a resurgence of vintage reworked garments. This approach is both creative and sustainable, perhaps even time efficient since artists can use the materials around them to construct their work. The trick is to offer qualities that the machines cannot quite replicate. Quilting and piecing has not been mastered by computerized machines; this is a skill that artists can still claim.

A pattern that has been relatively consistent and visible on social media is the support of artists by communities. This pattern appears in groups that have meaningful ties with the environments directly around them, tending to be ethically and environmentally conscious. While large scale fast fashion companies successfully sell their clothing to the masses, there is no space to create a meaningful connection with the maker or the piece of clothing itself. The source of the clothing remains so anonymous that it loses meaning. Artists find their customers within their local as well as online communities. These are communities that find value in items that contain a story, and the pieces become relatable artifacts.

Conclusion

So has skilled labor, as a necessity, become lost? Perhaps society has approached a fork in the road where skilled work has been split into two categories: the technical role that machines are taking on and the conceptual which remains a domain of the artists. Textile artists are finding ways to adapt, regardless of the potential economic threats that technology presents. Although technology is still advancing and gaining more potential, faith should never be lost as the brilliant mind of an artist will always find a way to make it work.

Resources

Blum, C., and J.G. Wurm. European Textile Research: Competitiveness Through Innovation 1st ed. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 1986.

Dinlersoz, Emin, and Jeremy Greenwood. “The Rise and Fall of Unions in the United States.” Journal of Monetary Economics 83 (October 2016): 129–146.

Gandhi, Kim. Woven Textiles: Principles, Technologies and Applications. Woven Textiles. San Diego: Elsevier Science & Technology, 2019.

History Crunch Writers. “Textile Manufacturing in the Industrial Revolution.” History Crunch, July 29, 2019. https://www.historycrunch.com/textile-manufacturing-in-the-industrial-revolution.html#/.

Horrocks, A R., and Subhash C. Anand. Handbook of Technical Textiles. Burlington: Elsevier Science, 2000.

Obler, Bibiana K., Phyllis D. Rosenzweig, Kirsty Robertson, and Thuy Linh Nguyen. Tu. Fast Fashion Slow Art. New York: Scala Arts Publishers, Inc., 2019.

Ritzer, George. The McDonaldization of Society. Los Angeles: Sage, 2015.

Taylor, LJ. “Landscapes of Loss: Responses to Altered Landscapes in an Ex-Industrial Textile Community.” Sociological Research Online 25, no. 1 (May 9, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780419846508.

Wellesley-Smith, Claire. Slow Stitch: Mindful and Contemplative Textile Art. London: Batsford, an imprint of Pavilion Books Company, 2015.

Wulfhorst, Burkhard, and Thomas Gries. Textile Technology. 1. Aufl. Carl Hanser Fachbuchverlag, 2012.