Most museums attempt to achieve 100% accessibility for all members of their community. Technical innovations are increasing opportunities for patrons who have low or no vision to engage with the arts. There are four dominant approaches for serving these members of the community: seeing through touch tours, beacon technology, audio description, and applications on personal devices. The last two may be categorized as emerging technologies. Seeing through touch tours are often specifically designed to serve low-vision or blind patrons, but the delivery of the custom tour is person to person. Technology interfaces offer alternatives for both users and institutions. To give a sense of what is now possible for museums and other visually-oriented art forms regarding experience creation for low-vision and blind individuals, the following offers an introduction to the technologies, and how they can or are being used in museum settings.

Seeing Through Touch

Creating opportunities for guests with low-vision or blindness patrons to touch original objects or 3D printed copies of works in the collection is a time tested approach to making art accessible to everyone. The Art Institute of Chicago has maintained a version of their Touch Gallery since 1920. In this gallery, visitors of all ages and abilities have the opportunity to explore four original works of art from the collection.[1] The Louvre opened a similar space in 1995 which presents bronze, plaster, and terra cotta replicas of sculptures in the collection and allows museum-goers to freely explore them through touch,[2] allowing visitors to gain a better understanding of texture, shape, form, and line.[3] The Victoria & Albert Museum, however, takes the idea of seeing art through touch a step further by including touch objects from the collection throughout their galleries—not just in one gallery—and offering docent-led touch tours upon appointment.[4]

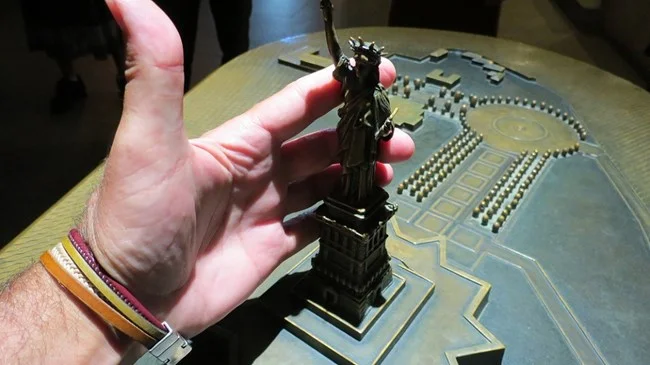

Presenting original works of art as touch objects does create some risk of damage to the object. Therefore, museums must take the proper measure to ensure that the work of art cannot fall and will not be harmed by contact with skin. One way to combat this risk—and to provide opportunities to touch paintings, silkscreens, and works on paper in addition to sculptures and ceramics—is the use of 3D printing. The Warhol Museum exhibits several 3D printed works on each floor of the museum for visitors of all abilities to explore the surface of Warhol’s works through touch.[5] [6]

Beacon Technology

The use of beacon technology[7] to enhance visitor experience[8] for patrons of all abilities within museums has emerged as an effective way to increase accessibility for differently-abled individuals and proves especially useful for those who are vision-impaired. The Cleveland Museum of Art’s Gallery One, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and the Brooklyn Museum are just three of many museums using beacons to promote accessibility and engagement with their collections. Focusing on vision-impaired individuals, beacon technology can be used to guide visitors through museums using smartphone apps.[9] Additionally, beacons can notify users of nearby works of art, provide descriptive and informational dialogue and answer questions about works of art.[10]

Expressive Audio Description

Adopting expressive language for audio description technology is a promising way for museums to increase accessibility for the low-vision and blind community. The Smithsonian’s American Art Museum offers ‘InSight’ tours once a month for low-vision and blind patrons of the visual arts. During these tours, docents describe body positions in works of art and encourage visitors to position their bodies in the same way to gain a better understanding of the form of work. Additionally, they bring in the other senses—hearing, tasting, smelling—to help describe scenes and colors.[11] Such descriptive prompts and language can easily be used in common audio tours allowing low-vision and blind patrons to have access to museums whenever they wanted—not just once a month when a tour was available, for example.

Applications

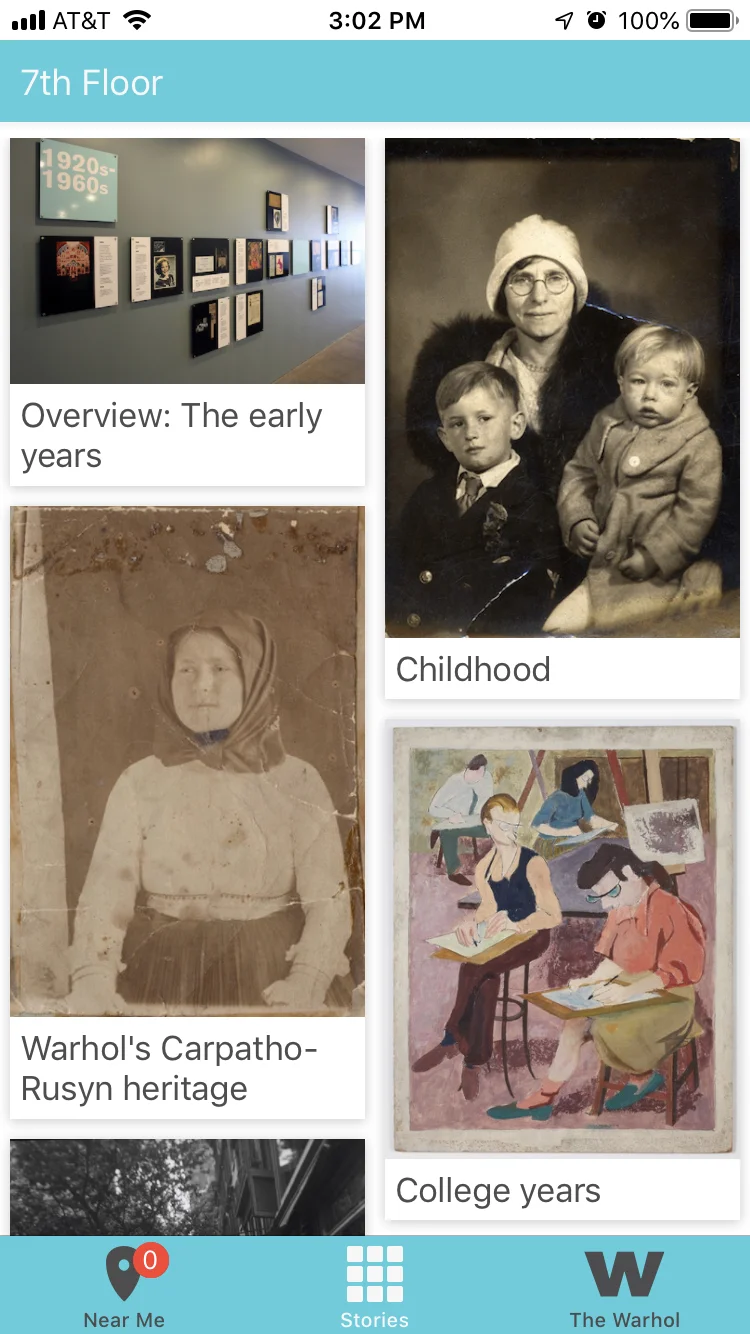

Museums are increasingly developing applications that users download on their personal smart devices that aid in navigating the museum. For example, the Warhol Museum developed ‘The Warhol: Out Loud’ to enhance engagement with the collection at all levels of ability, but with low-vision and blind patrons’ at the forefront. For instance, the app can be used with VoiceOver and Dynamic Type.[12] The Out Loud app—designed for iOS devices—provides users with stories about Warhol’s life and works on each floor of the museum, including information about 3D-printed reproductions. Beacons placed around the museum send Bluetooth signals to patrons’ devices to present stories based on their location in the museum. However, users may also select 1-3 minute stories they would like to listen to. Finally, ‘Smart Braille’ is an app available for Android devices through Google Play. Not only does it allow users to communicate more quickly by tapping combinations for braille figures, it can also read images text to outloud users.[15] Therefore, museums could incorporate this, or similar technology, allowing low-vision and blind patrons to access the collection at their leisure by taking photographs of wall text and having it read out loud back out them.

‘The Warhol: Out Loud’ Homepage; Personal iPhone Screenshot of the author

Any of the four options help improve accessibility and engagement within museums, but each has pros and cons. Seeing Through Touch tours is a dynamic option because patrons gain an understanding of shape and texture. However, touch tours are not always available, occurring sometimes only once a month.[13] Additionally, if museums do not have original objects that can be touched, 3D printing is expensive, limiting museums’ ability to take advantage of it. Even when a museum can produce 3D replicas of items in their collection, it is only part of a collection: most of the collection remains inaccessible to the low-vision and blind community. Beacon technology can help patrons navigate museums with their personal phones or devices owned by the museums. However, beacon technology is expensive to install and more challenging to coordinate. Audio description might be the easiest resource to implement because museums already develop audio tours. Incorporating vivid language in audio guides has the ability to reach the low-vision and blind community in new, non-isolating, and impactful ways.[14] Implementing descriptive language in new audio guides would not be a challenge, but re-recording existing audio tours is costly in terms of time. Applications on personal smart devices, such as ‘The Warhol: Out Loud’ and ‘Seeing AI’, allow low-vision and blind patrons to access museums at any time. However, developing apps specifically for institutions, such as The Warhol’s app takes time. After considering all the options, organizations may find that a combination of these resources is ideal. That way, the technologies can work together to provide the most complete experience for each individual, regardless of ability. ‘The Warhol: Out Loud’ is a good example of technologies working together; patrons download the app on their personal iOS device, it provides audio description of works and information about Warhol, and it uses beacon technology to suggest stories to the patron, who can use the app with voice over technology.

Works Cited:

Beete, Paulette. “Touch and See: Accessibility Programs for People with Vision Impairments at the Art Institute of Chicago.” NEA Arts Magazine 1 (2013). https://www.arts.gov/NEARTS/2015v1-challenging-notions-accessibility-and-arts/touch-and-see. Accessed 24 Oct. 2018.

Dimitrova-Radojichikj, Daniela. “Museums: Accessibility to visitors with vision impairments.” Published Jan. 2017. Accessed 25 Oct. 2018. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313030970_Museums_Accessibility_to_visitors_with_visual_impairment.

Ginley, Barry. “Museums: A Whole New World for Visually Impaired People.” Disability Studies Quarterly 3, no. 3 (2013). http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/3761/3276. Accessed 24 Oct. 2018.

GitHub. “CMP-Studio / TheWarholOutLoud.” GitHub. Accessed 15 Nov. 2018. https://github.com/CMP-Studio/TheWarholOutLoud.

Google Play. “Smart Braille.” Tasevski. Available Spring 2018. Accessed 26 Nov. 2018. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.finki.tasevski.smartbraille&hl=en_US.

Lahaye, Marion. “The Use of Beacons at The Cleveland Museum of Art’s Gallery One.” iBeacon Trends, http://www.ibeacontrends.com/cleveland-museum-beacons/. Published 23 Mar. 2017. Accessed 27 Oct. 2018.

Mallik, Neha. “3 Museums Using Beacons to Enhance Interactivity.” beaconstat, https://blog.beaconstac.com/2015/02/3-museums-using-beacons-to-enhance-interactivity/. Published 5 Feb. 2015. Accessed 24 Oct. 2018.

SDS. “The Guggenheim Museum: Tracking Visitor Movements to Deliver a Better Museum Experience.” HBS Digital Initiative, https://digit.hbs.org/submission/the-guggenheim-museum-tracking-visitor-movements-to-deliver-a-better-museum-experience/. Last modified 22 Nov. 2015. Accessed 27 Oct. 2018.

Stamberg, Susan. “Blind Art Lovers Make the Most of Museum Visits With ‘Insight’ Tours.” National Public Radio, https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/01/05/505419694/blind-art-lovers-make-the-most-of-museum-visits-with-insight-tours. Published 5 Jan. 2017. Accessed 26 Sept. 2018.

The Associated Press. “Go ahead and touch, says Louvre Museum.” The Los Angeles Times, http://articles.latimes.com/2008/feb/27/entertainment/et-touchart27. Published 27 Feb. 2008. Accessed 26 Oct. 2018.

The Louvre. “The Touch Gallery. The Louvre, https://www.louvre.fr/en/touch-gallery. Accessed 20 Oct. 2018.

The Warhol Museum. “Accessibility.” The Warhol Museum, https://www.warhol.org/accessibility-accommodations/. Accessed 24 Oct. 2018.

[1] Beete, Paulette. “Touch and See: Accessibility Programs for People with Vision Impairments at

the Art Institute of Chicago.”

[2] The LA Times, “Go ahead and touch, says Louvre Museum.”

[3] The Louvre, “The Touch Gallery.”

[4] Ginley, Barry. “Museums: A Whole New World for Visually Impaired People.”

[5] The Warhol Museum. “Accessibility.”

[6] Linke to AMT-Lab article

[7] Link to Kate Martin’s “Intro to Beacons for Arts Managers.”

[8] HBS Digital Initiative. “The Guggenheim Museum: Tracking Visitor Movements to Deliver a Better Museum Experience.”

[9] Lahaye, Marion. “The Use of Beacons at The Cleveland Museum of Art’s Gallery One.”

[10] Mallik, Neha. “3 Museums Using Beacons to Enhance Interactivity.”

[11] Stamberg, Susan. “Blind Art Lovers Make the Most of Museum Visits With ‘Insight’ Tours.”

[12] GitHub. “CMP-Studio / TheWarholOutLoud.”

[13] Stamberg, Susan. “Blind Art Lovers Make the Most of Museum Visits With ‘Insight’ Tours.”

[14] Dimitrova-Radojichikj, Daniela. “Museums: Accessibility to visitors with vision impairments.”

[15] Google Play. “Smart Braille.”